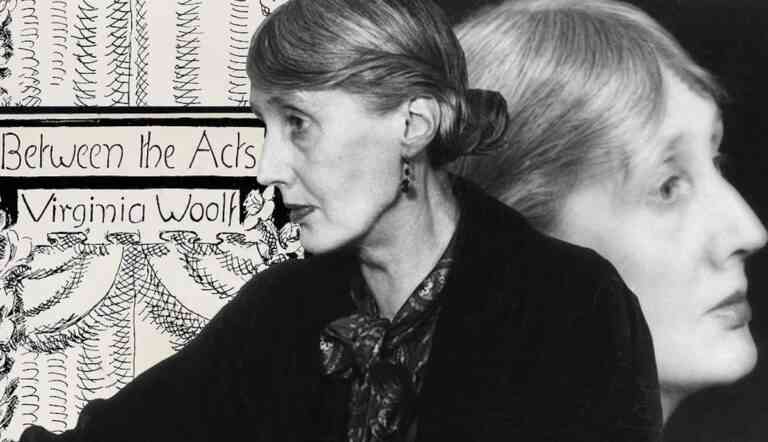

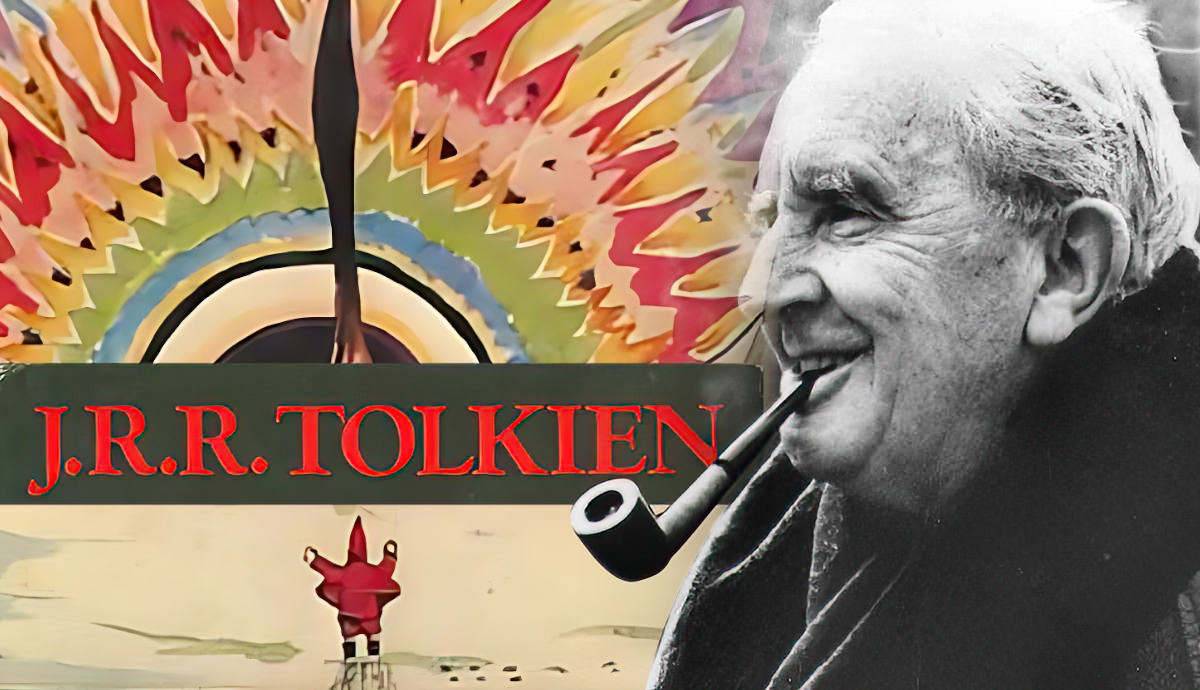

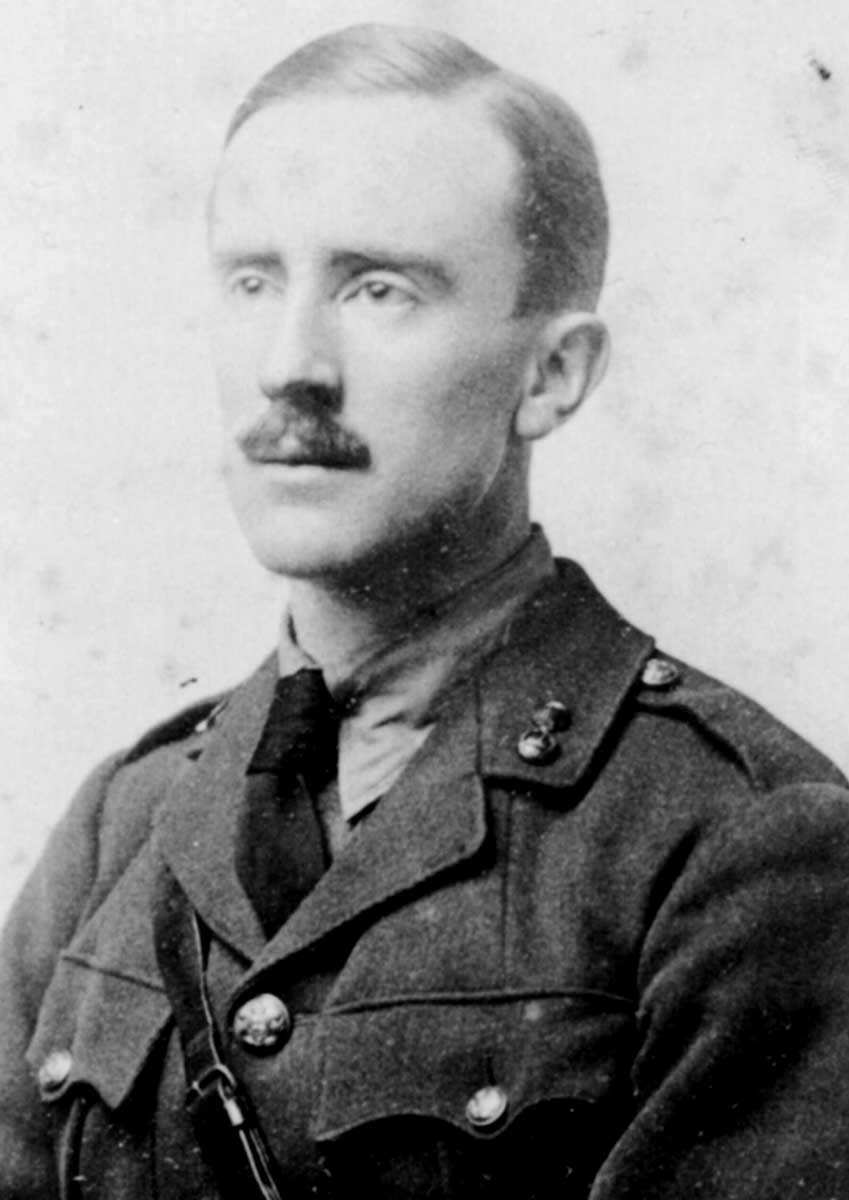

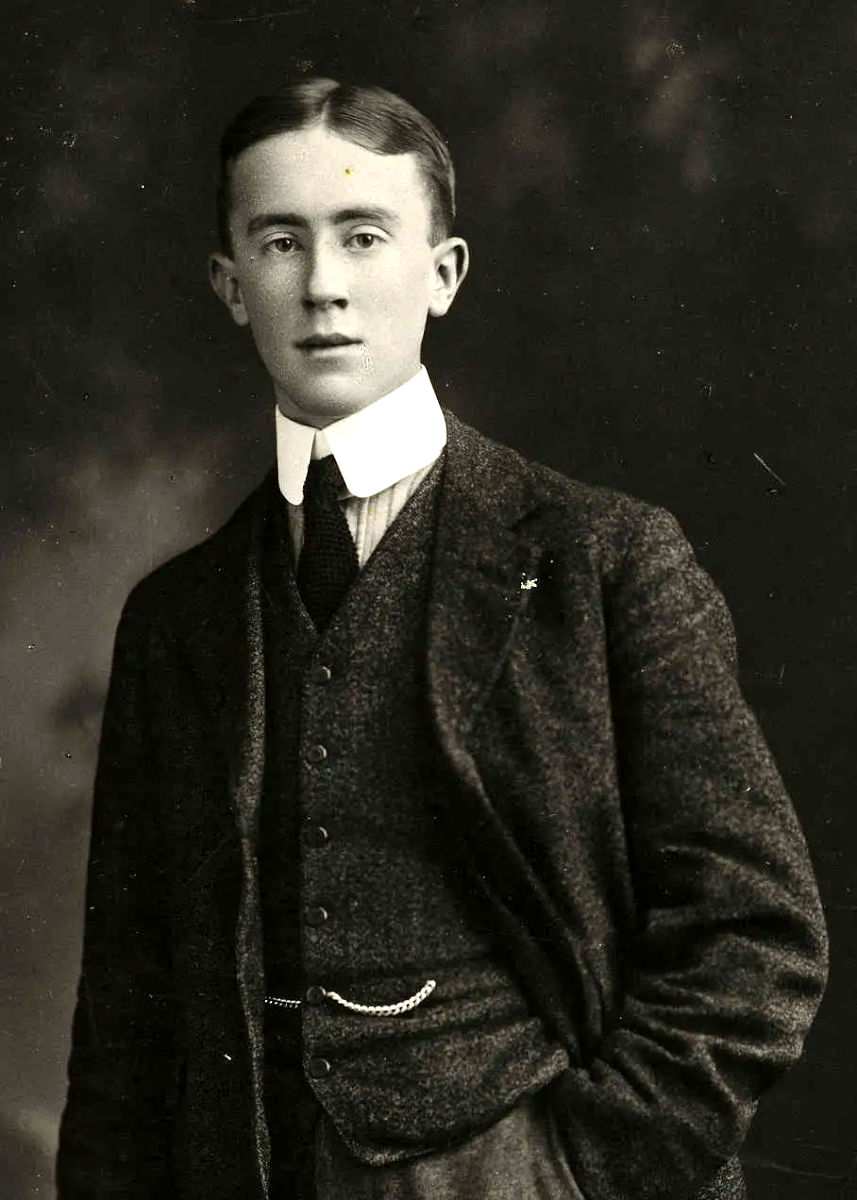

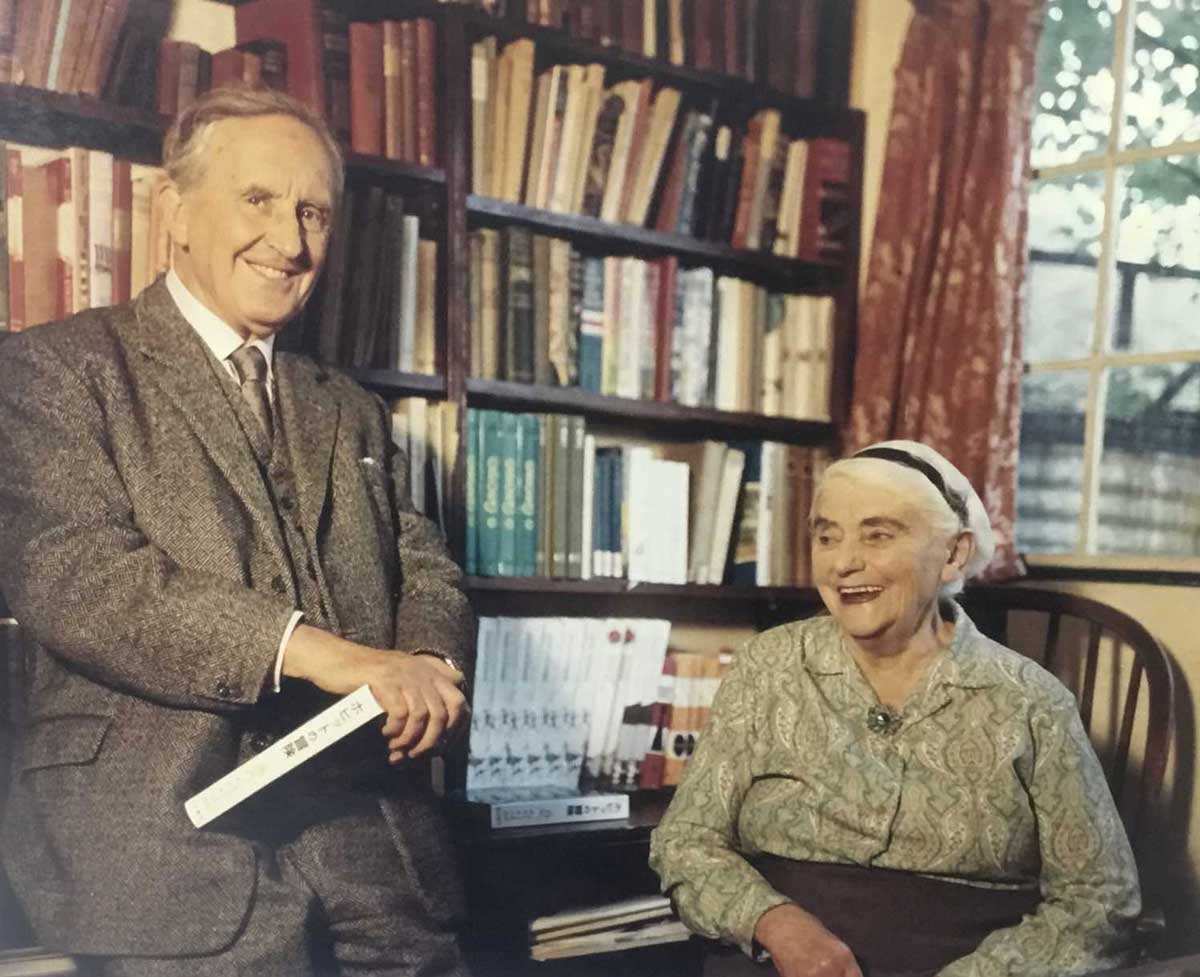

Hailed as the father of the modern fantasy genre, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-Earth legendarium — and his trilogy The Lord of the Rings in particular — are some of the most beloved books of all time and are rightly celebrated across the world. Having fought in the First World War and then worked as a philologist and academic at Oxford University for most of his working life; however, Tolkien accomplished many other things in his life and wrote many other works besides the Middle-Earth legendarium for which he is so famous today. Here, we will delve deeper into Tolkien’s body of work, ranging from fiction to academic writing, to uncover more works by this great author…

1. “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” 1936

Unlike the other works that will be mentioned here (which have all been grouped together in Tales from the Perilous Realm), “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” is not a work of fiction but of literary criticism. As well as being a prolific writer, Tolkien was also a philologist and, from 1925 to 1945, he was the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon and a Fellow of Pembroke College at Oxford University, before taking up his post as Merton Professor of English Language and Literature at Merton College, Oxford University. It was in the capacity of an academic and expert in early Germanic languages and literature that he wrote this seminal essay.

“Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics,” however, began life as a lecture, namely the Sir Israel Gollancz Memorial Lecture, given by Tolkien at the British Academy in 1936. It was then subsequently published as an academic paper in The Proceedings of the British Academy in the same year.

In it, Tolkien sets out to defend the Old English poem’s literary merit, and, in doing so, goes against the received wisdom of the time that Beowulf was largely only interesting as a historical document. It was due to this preference for viewing Beowulf as a historical document that the monsters (Grendel, Grendel’s mother, and the dragon) were either dismissed as extraneous or simply ignored entirely. In making his case for reading Beowulf as a poem – that is, as a work of art – Tolkien therefore set out to argue that the monsters were key not only to the poem’s narrative structure but also to the unity of its artistic effect. This marked a turning point in Beowulf studies, with Professor Michael D.C. Drout hailing it as the single most significant essay ever to be written about Beowulf.

2. “Leaf by Niggle,” 1945

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly Newsletter

“Leaf by Niggle” is a short story written in 1938-39. It was originally published in The Dublin Review in January 1945 before being published in Tree and Leaf in 1964, alongside Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy-Stories.”

The story centers around the eponymous Niggle, an artist who obsessively pursues beauty in his work, even though the society in which he lives does not value art. This obsession leads him to paint a picture of a forest with a large tree in the foreground. He invests every leaf on this tree with an intricate level of detail. Nonetheless, he fails to realize his vision, as various mundane tasks prevent him from giving the tree his undivided attention. He also spends a great deal of time (somewhat grudgingly) helping his neighbor, Parish, a disabled gardener.

Though he does not know where or when he must go, Niggle is aware that he will have to embark on a trip at some point. When the time comes, however, he is unprepared and is placed in an institution. Meanwhile, Niggle’s painting is used to patch a hole in a leaking roof, with only one perfect leaf being saved and placed in a museum.

Upon being released from the institution, Niggle is sent to a forest for his convalescence. This, it turns out, is the very same forest he sought to depict in his painting. Here, he is reunited with Parish, who uses his skills as a gardener to beautify the forest even further.

Tolkien was a devout Catholic, and “Leaf by Niggle” is often read as a work of religious allegory. Though he claimed not to particularly like allegory, Tolkien did refer to it as his “purgatorial” story. This suggests that it might elucidate Tolkien’s views on art, specifically on his religious philosophy of creation versus sub-creation.

3. Farmer Giles of Ham, 1949

Written in 1937, Farmer Giles of Ham is a humorous work modeled after the medieval fable tradition and was first published in 1949. While Tolkien’s writings on Middle-Earth were elaborately planned and schematized, Farmer Giles of Ham is often wilfully and ebulliently anachronistic, set as it is in a period of the so-called Dark Ages all of Tolkien’s own imagination.

The story is a comically parodic take on many of the tropes of heroic literature, and stout, plodding Farmer Giles is certainly not an obvious hero. When he manages to scare a giant (albeit a somewhat near-sighted hard-of-hearing giant) away from his land with the help of a (patently anachronistic) blunderbuss, however, the people in the Middle Kingdom hail him as a hero.

Like Smaug in Tolkien’s writings on Middle-Earth, Farmer Giles of Ham also features a dragon named Chrysophylax Dives. After being misinformed of Farmer Giles’ encounter with the giant (the giant claims that no people live in the Middle Kingdom, only sheep, cattle, and stinging flies), Chrysophylax invades the Middle Kingdom. In keeping with the comic overtones of the book, Chrysophylax, though cunning and greedy, is not an overly bold dragon, having only been lured to the Middle Kingdom on the understanding that there are no knights there to prevent him from eating all the sheep and cattle. The knights that are sent by the king, however, prove to be inept posers, and the people of the Middle Kingdom call for Farmer Giles to save them once again. But will this most unlikely of heroes be up to the task?

4. Smith of Wootton Major, 1967

Published in 1967, Smith of Wootton Major is a fantasy novella with an interesting origin story. In writing a preface for George MacDonald’s fairy story The Golden Key, Tolkien meant to illustrate the notion of the Faery by way of a short story of his own. And, of course, this story went on to form the basis of Smith of Wootton Major.

In the novella, the village of Wootton Major is renowned for its festivals, chief among which is the Feast of Good Children, which is celebrated only once every twenty-four years. During the Feast of Good Children, twenty-four children from Wootton Major are invited to a party where the Great Cake is served. At this particular Feast of Good Children, the Great Cake is nominally made by Nokes, the Master Cook, though much of the real labor is, in fact, carried out by his apprentice, Alf. Objects are hidden inside the cake for the children attending the party to find, including a star Nokes had found in a spice box. Though all the other objects are uncovered during the Feast, the star is not found.

The reason for this is that the star has been swallowed by one of the children, the son of the village’s blacksmith. By his tenth birthday, the star is affixed to his forehead, signifying his ability to travel from the real world of Wootton Major to the Faery realm with impunity. While he follows in his father’s footsteps and goes on to become a blacksmith, he has access to a magical world, and his adventures there are recounted in the novella. But when it is time for the next Feast of Good Children, he must surrender the star, and his access to the Faery realm is in jeopardy…

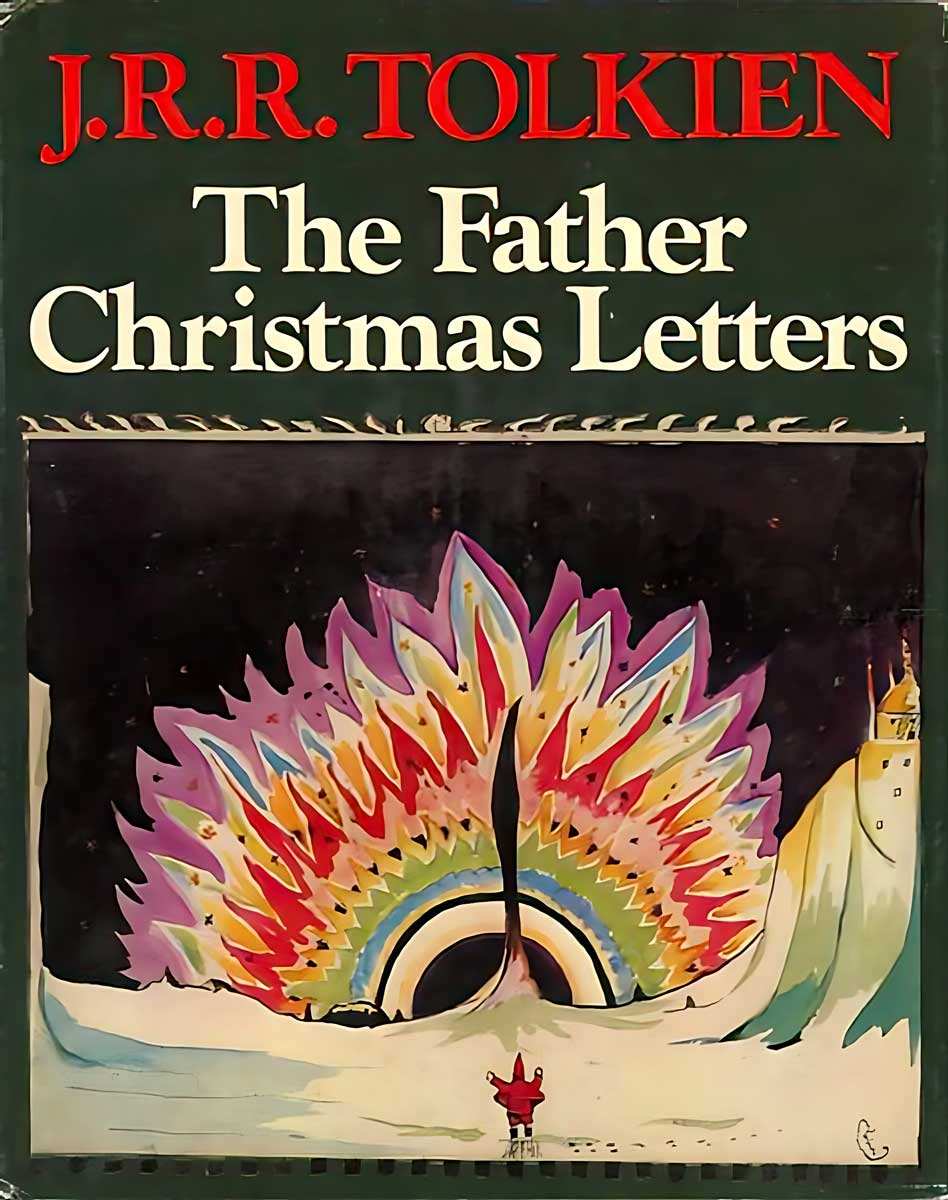

5. Letters from Father Christmas, 1976

Letters from Father Christmas (alternatively known as The Father Christmas Letters) is a collection of letters Tolkien wrote for his children from 1920 (when his oldest son was three years old) to 1943. This was an annual tradition in the Tolkien household: every year, Tolkien would write each of his children letters from Father Christmas, which would be delivered to the children in envelopes featuring North Pole stamps and postage marks that Tolkien had also designed.

They are told from the perspective of Father Christmas and recount his escapades alongside his elves and, of course, polar bears. It has been argued that some of the stories Tolkien made up for his children in these letters went on to inspire plot points in The Lord of the Rings. When read purely on their own terms, however, Letters from Father Christmas show another side to Tolkien beyond the Oxford don and the father of modern fantasy. Whimsical and funny, they show Tolkien as a devoted father for whom entertainment was all important in writing.

That Tolkien is largely remembered as the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings is a small wonder. In creating Middle-Earth, he conjured a fantasy world of unsurpassed detail and imaginative complexity. By ranging more widely within Tolkien’s oeuvre, however, we can discern a more rounded picture of Tolkien, not only as a writer but also as an academic and a man of faith. And, in turn, we can appreciate the ways in which these other facets influenced his writing. While only one perfect leaf by Niggle is preserved for posterity and the rest of his great work is lost, Tolkien’s genius branched out in many different directions, all of which merit our attention.